I’ve managed over 50 technology employees over my career – and have been managed as a tech lead for quite some time. Here are some hard-won lessons from my experience.

1. Be bossy.

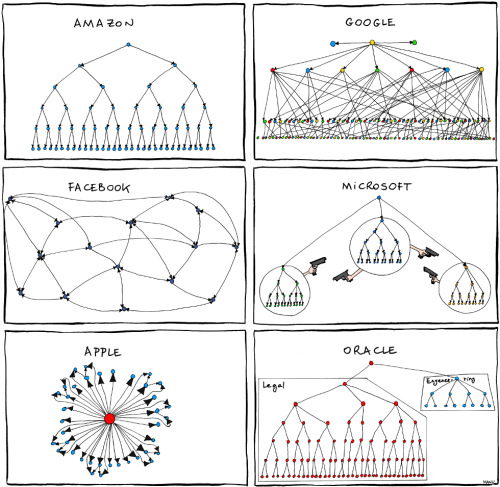

We’ve all seen Steve Jobs running around Apple having tantrums in movies. Especially as a young manager, he did this often – before he learned there were better ways to manage. There’s a small place in the world for that. Being bossy doesn’t always fail, but it is a recipe for disaster. When you look at the inspiring example of Sheryl Sandberg and the transformations she wrought at Facebook, you can see the benefits of true leadership. Leadership that is earned rather than cheap theatrics. Google has a culture that encourages cooperation and has created one of the most profitable companies in the world.

Ed Catmull is the founder of Pixar and the author of one of the best books on management, Creativity Inc. He explained what he saw as the core of good management:

I believe the best managers acknowledge and make room for what they do not know—not just because humility is a virtue but because until one adopts that mindset, the most striking breakthroughs cannot occur. I believe that managers must loosen the controls, not tighten them. They must accept risk; they must trust the people they work with and strive to clear the path for them; and always, they must pay attention to and engage with anything that creates fear. Moreover, successful leaders embrace the reality that their models may be wrong or incomplete. Only when we admit what we don’t know can we ever hope to learn it.

Many managers seek to emulate the raging teenager in Steve Jobs mode. They take as their naive mantra, “Be Bossy.” That’s the quickest way to lose all your best people.

2. Create a culture of blame.

I used to work for a company that had a top-down culture of blame. I hadn’t realized how bad it was until after (I was working in a different division). I heard horror stories from people who now lead this group. They spoke of how the head of their group would yell at their boss for every failure. And then how their former boss would break phones and throw stuff against the wall and loom over their desk. There was a rigid process to follow that was almost impossible given the rate of work. Anyone who tried something new was personally blamed. The turnover rate was catastrophic. It took a herculean effort to transform this culture into one where people felt able to fail and innovate.

The worst companies are those that are built on a culture of blame – because this leads to the creation of bureaucracy – quoting Rory Sutherland:

Bureaucrats really love a formula because it prevents them from having to exercise judgment for which they might be blamed…

You can avoid blame by claiming what you did was entirely rational, and as if the act was therefore unavoidable because reason told me to do this. We scoped the market, did market research. It told us that people needed that. So we produced that. If you follow all the precepts and fail, you won’t get fired or blamed because you were rational. If you do something which is better, but involves a degree of human imagination or judgement, if it works, well and better, you might get a bit of credit but you probably will get people saying it would have been even better if you had followed reason. If it goes wrong, you’re fired.

Innovation comes when you take risk. And bureaucracy is it’s death.

To quote Eric Schmidt: “To innovate, you must learn to fail well.” Failure is inevitable. And a business needs to acknowledge that. The businesses that are best with technology are built on this assumption. For the company in question, this led to a rapid adoption of various technologies and the development of many new ones.

3. Don’t value your employees.

One of the most dispiriting things I’ve ever experienced was a cartoon villain of an attorney threatening a room full of employees that we could be “upgraded” in a week. It’s hard to feel motivated and to push yourself and to make the small right decisions everyday when you feel devalued. And the truth of technology is that doing it right is hard. It involves long-term thinking. You need to design systems – and make decisions that allow you to scale. If you’re pushed to think short-term because you’re short-staffed or undermined or a pawn in political games, things will go okay for a while. Until they don’t. Those who sell and those who produce create value every day. But technology sets the foundation for them to create more value next year than they did today.

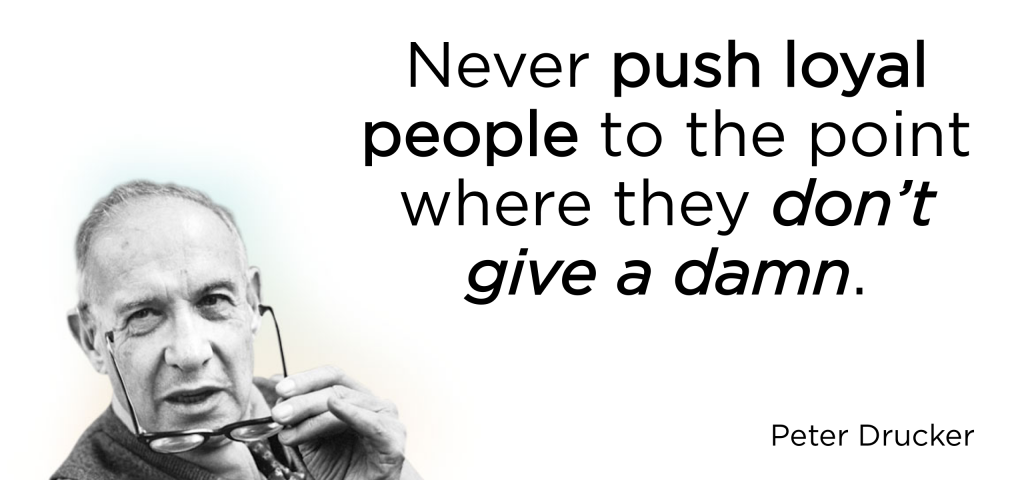

Never push loyal people to the point where they don’t give a damn

People aren’t interchangeable. They can’t just be upgraded like a faulty RAM drive. In the tech world where there is so much demand, that’s especially true. You especially need your tech team committed to making your company better and thinking long-term.

If you’re a decent person, a decent manager, an effective CEO, when asked the question of what made you successful…the answer is never “hard work” or “a great idea“. All of that helps. As does luck. (We all need to check our privilege.) But the one core common thing is a great team. This is a truism that Rory Cowan (former CEO of Lionbridge) stated at SlatorCon last week: “What someone buying your company is buying is ‘the next level’ of executives below the founder.” It’s probably one of his few areas of agreement with rival, Phil Shawe (co-CEO of TransPerfect). As Phil stated in his GlobalLink NEXT presentation as the key to the company’s growth:

– Find the best people.

– Align incentives.

– Get out of the way.

4. Be a Communist.

You can’t centralize everything. Anyone who promises to centralize all technology in a single group is promising to destroy innovation. Technology needs competing groups. It needs side projects. It needs, to quote Phil, controlled chaos.

What a tech company does need is to agree to the “rules of the road.” They need to agree on rules for competition and cooperation. But if you put one dictator above everyone, you will fail.

5. Being clueless about technology.

You don’t need to be an expert in technology to lead a tech company. After all, it was Steve Jobs, not Steve Wozniak, who ran Apple. But you do need to engage with the concepts and care about it. You need to have a base level understanding of what’s going on at minimum. And from there, you can often manage people rather then technology. The best tech CEOs need to be able to assert in clear principles their vision.

What you don’t want is to not know how to operate the most basic consumer technology. I once worked with an executive to whom I handed a set of Apple earpods. This was back in the day when Apple earpods still had wires and when there was still a headphone jack on the phone. (*Those were the days!*)

I handed the package over to the executive, and they looked at me quizzically. I assumed they just wanted me to open the package, so I did that, and handed the opened case over. They were still confused. So, I unwound the headphones and held them out. They asked me to explain how it worked – and I really wasn’t sure what to say. “These pieces go in the ears,” I said. “And you can talk normally, but the microphone is here.”

Now, there’s nothing wrong with that. My frustration came when the same executive told me that they didn’t understand what tech people did all day. And then assumed that they must be lazy and drains on company profitability. Many companies have thought that over the years, but few of those companies continue to exist today. I was just lucky enough that another executive came along to guide my career from there.

Conclusion

It’s easy to say you’re a tech executive. It’s harder to be one. In the end, most of the things to avoid are the same things that you should avoid if you want to be a good person.

Retain humility. Don’t be bossy. Give credit to your employees. Encourage competition.

Despite everything, that’s one of the things I’ve always seen at TransPerfect. And one of the reasons I’ve been proud to be part of the great team we have had here.